Interview by James Phelan, in Literati

| robert_drewe_literati_interview.pdf | |

| File Size: | 85 kb |

| File Type: | |

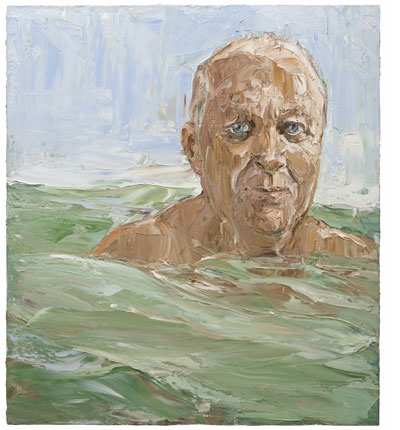

"Robert Drewe (in the swell) 2006" by Nicholas Harding was an Archibald Prize finalist and was purchased in 2010 by the National Portrait Gallery in Canberra for its permanent collection.

Undercurrent

Nicholas Harding is a specialist in depicting floating and swimming figures. The title of the painting recently purchased by the National Portrait Gallery, Robert Drewe (in the swell) describes the effect Harding is able to pull off, seemingly without effort, again and again; the real, solid body of a person, invisible, yet present, obscured by water that supports and nudges at it.

A better combination of artist and sitter would be difficult to devise. The titles of Drewe’s books – The Bay of Contented Men, The Bodysurfers, The Rip, The Drowner and the autobiographical/ fictional The Shark Net – proclaim that his writing is anchored in the fundamental element of water. So it was that in mid-2005, the author was invited to open a group exhibition, The Sea, at Rex Irwin’s commercial art gallery in Woollahra. Nicholas Harding was one of the artists represented. Harding had no opportunity to talk to Drewe at the opening; but shortly afterward, he emailed him about the possibility of a portrait. Agreeing to meet in ‘neutral territory’ at The Pass Café near Byron Bay on the coast north of Sydney, they hit it off and the portrait process began with a series of drawings made on the beach.

In a piece published on Harding’s website, Drewe, who, like many men, has been used to thinking of himself as ‘no oil painting’ and finds it hard to relax even momentarily for a photograph, describes the unsettling experience of being scrutinised at length by the artist. The first portrait was one of Harding’s now-characteristic ‘littoral’ works, showing Drewe amongst other figures on the beach, the sea at his back. It was promising; Drewe saw something of his own grandfather in it; but Harding overworked it, and it was spoiled. A second attempt pleased no one in the end. With a number of drawings, some photographs (mainly of water) and two failed portraits, the artist squared up for a third attempt, returning to Byron Bay to renew their ‘sittings’. On this occasion, however, as Harding drew, he looked up from his sketchpad to see that the older man had disengaged, for a moment, from the portrait process. The expression Harding saw in that unposed moment was what he had been missing. At last, he knew he had ‘something to chase’.

The artist was still oppressed, however, by what to do with the author’s figure. Some time later, Harding was hanging in a quiet sea at Minnie Water. It was midday, and he was looking at the way the sea and sky melted together and colours faded and bled into each other in the heat. As he observed the way ambient light bounced off the water and the eyes of the people bobbing in it, and the way the water lapped around the figures more rapidly than it lifted and lowered them, the portrait of Drewe crystallized in his imagination. He went back to Sydney to create a painting of the author treading water.

Robert Drewe recalls rather poignantly that when he stood self-consciously – yet, it may be inferred, with some expectancy – by the portrait at the Archibald exhibition, nobody noted the real man beside his painted image. The Sydney crowd hastened, instead, to see the paintings of celebrities on display. It was the culmination of the experience of having the portrait painted, as a whole: the interesting sensation of having one’s ego simultaneously inflated and deflated, as Drewe puts it.

Now, in fact, it may be one of the few paintings in the Gallery’s collection that comes close to the widely-held belief – or romantic fancy – that a painted portrait is unique in its uncanny capacity to reveal something its subject’s sitter’s psyche or ‘soul’. Drewe, at least, seems to think so. ‘Apart from becoming good friends with the artist, a terrific bloke,’ he writes, ‘I got something valuable out of the experience, an appreciation of true artistic insight. In our many hours of posing and sketching, eating and drinking and chatting, I’d always presented a cheerful face, I thought, cracking jokes and bantering my way through my self-consciousness. I hadn’t let on that my life was going through a very rough patch. But I saw it in my portrait. It was all evident.’

Dr Sarah Engledow

National Portrait Gallery

A better combination of artist and sitter would be difficult to devise. The titles of Drewe’s books – The Bay of Contented Men, The Bodysurfers, The Rip, The Drowner and the autobiographical/ fictional The Shark Net – proclaim that his writing is anchored in the fundamental element of water. So it was that in mid-2005, the author was invited to open a group exhibition, The Sea, at Rex Irwin’s commercial art gallery in Woollahra. Nicholas Harding was one of the artists represented. Harding had no opportunity to talk to Drewe at the opening; but shortly afterward, he emailed him about the possibility of a portrait. Agreeing to meet in ‘neutral territory’ at The Pass Café near Byron Bay on the coast north of Sydney, they hit it off and the portrait process began with a series of drawings made on the beach.

In a piece published on Harding’s website, Drewe, who, like many men, has been used to thinking of himself as ‘no oil painting’ and finds it hard to relax even momentarily for a photograph, describes the unsettling experience of being scrutinised at length by the artist. The first portrait was one of Harding’s now-characteristic ‘littoral’ works, showing Drewe amongst other figures on the beach, the sea at his back. It was promising; Drewe saw something of his own grandfather in it; but Harding overworked it, and it was spoiled. A second attempt pleased no one in the end. With a number of drawings, some photographs (mainly of water) and two failed portraits, the artist squared up for a third attempt, returning to Byron Bay to renew their ‘sittings’. On this occasion, however, as Harding drew, he looked up from his sketchpad to see that the older man had disengaged, for a moment, from the portrait process. The expression Harding saw in that unposed moment was what he had been missing. At last, he knew he had ‘something to chase’.

The artist was still oppressed, however, by what to do with the author’s figure. Some time later, Harding was hanging in a quiet sea at Minnie Water. It was midday, and he was looking at the way the sea and sky melted together and colours faded and bled into each other in the heat. As he observed the way ambient light bounced off the water and the eyes of the people bobbing in it, and the way the water lapped around the figures more rapidly than it lifted and lowered them, the portrait of Drewe crystallized in his imagination. He went back to Sydney to create a painting of the author treading water.

Robert Drewe recalls rather poignantly that when he stood self-consciously – yet, it may be inferred, with some expectancy – by the portrait at the Archibald exhibition, nobody noted the real man beside his painted image. The Sydney crowd hastened, instead, to see the paintings of celebrities on display. It was the culmination of the experience of having the portrait painted, as a whole: the interesting sensation of having one’s ego simultaneously inflated and deflated, as Drewe puts it.

Now, in fact, it may be one of the few paintings in the Gallery’s collection that comes close to the widely-held belief – or romantic fancy – that a painted portrait is unique in its uncanny capacity to reveal something its subject’s sitter’s psyche or ‘soul’. Drewe, at least, seems to think so. ‘Apart from becoming good friends with the artist, a terrific bloke,’ he writes, ‘I got something valuable out of the experience, an appreciation of true artistic insight. In our many hours of posing and sketching, eating and drinking and chatting, I’d always presented a cheerful face, I thought, cracking jokes and bantering my way through my self-consciousness. I hadn’t let on that my life was going through a very rough patch. But I saw it in my portrait. It was all evident.’

Dr Sarah Engledow

National Portrait Gallery